I looked at the title and started singing the hymn before I’d even gotten to the page.

I knew this was another one of those wonderful Southern Harmony tunes, and I relished in it as I flipped open the hymnal. “What more can I say about Southern Harmony?” I said to myself. “I don’t want to bore my readers.”

Flip…flip…flip….ah, number 69. Oh wait. Union Harmony.

UNION Harmony?

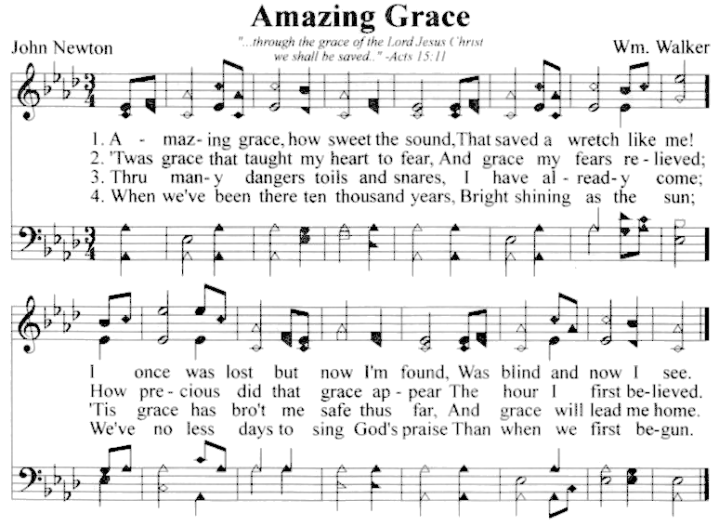

Apparently, while William Walker was in South Carolina compiling Southern Harmony, WIlliam Caldwell was in Tennessee compiling Union Harmony. Both are collections of tunes noted in shape note (the note heads have different shapes to, as the theory goes, facilitate easier learning – here’s an example of Amazing Grace in shape note:

Both men collected tunes that had cropped up in the first two hundred years of European settlement in the eastern US – tunes that, as I reflected a few days ago, are borne of tragedy and sorrow but tinged with hope.

Such is the case in this one (the tune is called Foundation). And because of the vague melancholy of the tune, the words seem less plainly cheerful and more earnest.

Give thanks for the corn and the wheat that are reaped,

for labor well done and for barns that are heaped,

for the sun and the dew and the sweet honeycomb,

for the rose and the song and the harvest brought home.Give thanks for the mills and the farms of our land,

for craft and the strength in the work of our hands,

for the beauty our artists and poets have wrought,

for the hope and affection our friendships have brought.Give thanks for the homes that with kindness are blessed,

for seasons of plenty and well-deserved rest,

for our country extending from sea unto sea,

for ways that have made it a land for the free.

And it becomes even more melancholy at that last couplet. Is this the land of the free? Free for whom? Or is this aspiration again, knocking on our doors, reminding us of the vision and intention of America even as we regularly watch ourselves fall short?

We have much to be thankful for – even if not everyone has all of those things. We have much to be thankful for – even as we work to ensure everyone eventually does. We have much to be thankful for – even if it’s simply a hymn that reminds us not just what we have, but what we know is true in the world, and what calls us to help.